PLEASE NOTE:

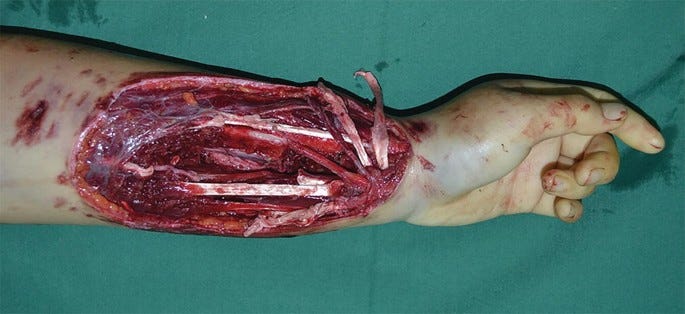

This post contains a graphic clinical photograph of a major wound. I was initially going to include the original patient photo, but due to its extremely graphic nature and some residual hesitancy about privacy, I have elected to substitute an already-published photo of a similarly severe injury from a surgical text. The substitute is less gory but still potentially disturbing to sensitive viewers, hence this advance warning. It will be at the end of the post.

The patient in this case gave consent for me to publish an anonymized narrative of her illness and treatment (i.e. I have altered certain details in this case to assure her identity is protected, without altering anything of medical/psychiatric significance).

I am posting this case report here for educational purposes, both for the benefit of my colleagues, but more importantly for anyone in the general public who is interested in learning more about the seriousness of psychiatric illness. Specifically, I am concerned about the growth certain strains of anti-psychiatry which views most or all mental illness as “a choice”, “a different way of life”, “people having different priorities”, and other such notions. I hope those who doubt the reality and seriousness of severe mental illness remain open to new evidence. However limited my readership is here, it will be far wider than if I waited a year to get published in a journal that nobody reads.

Case — circa Summer, 2019

“Sara” is a 29-year-old woman with no psychiatric history and a medical history of mild asthma and sickle-cell trait, who was brought to the ED by ambulance from a non-hospital community mental health center after being found with a major self-inflicted forearm wound.

One year prior to admission, Sara immigrated with her family to the United States from Nigeria for her father’s work. According to family, approximately 6 months after arriving in the US, Sara started showing signs of what appeared to be depression: social withdrawal, reduced affective expression, diminished motivation and energy, and lack of interest in ordinary activities. Despite being fluent in English, having clearly above average intelligence, and possessing a college degree in finance, Sara failed to find consistent work. Instead, she would isolate herself in her room, sometimes for weeks at a time, only leaving to use the bathroom and forage for food at increasingly odd hours when others weren’t around. Interactions with her family progressively decreased. Eventually she started refusing meals or eating unusually small portions, leading to noticeable weight loss.

In the early morning of the day of admission, Sara’s parents brought her to a community mental health center for evaluation after a series of unexpected verbal outbursts at home that nearly became physical. This behavior was very unusual for Sara, who was typically upbeat and even-tempered.

Sara was calm and cooperative during the initial triage at the community center. She was given a private room in which to relax before her scheduled formal evaluation later in the afternoon by a psychiatric social worker.

Approximately 45 minutes after being roomed, the staff were made aware of an emergency by the screams of a colleague performing routine safety checks. As the staff member entered Sara’s room, she found her sitting cross legged on the floor in a large pool of blood, staring with wide-eyed intensity at what appeared to be a massive laceration lengthwise down the anterior aspect of her forearm.

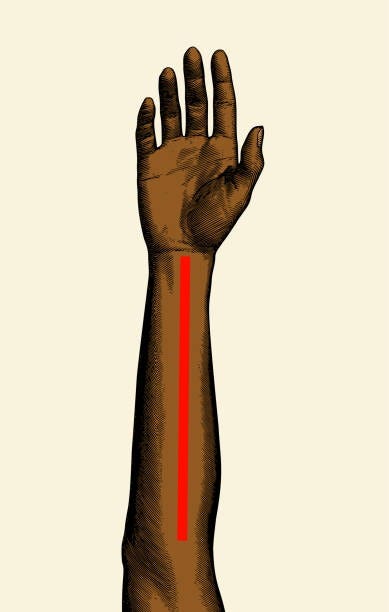

For those who prefer not to view the clinical photo at the end of the post, imagine a deep cut lengthwise down the anterior forearm at least 1 inch deep, from the wrist almost to the antecubital fossa (the “inside” of the elbow joint), as shown by the red line below. The cutting instrument penetrates approximately 1/3 to 1/2 of the way through the thickness of your arm, with the flesh on each side fanning out, as if you were butterflying a hotdog. Flesh, nerves, blood vessels, and tendons are clearly visible.

Other staff arrived and called 911 to transport Sara to the hospital. While waiting for the ambulance, they recovered the instrument she used to open her arm.

To their horror, what the staff found was not a sharp knife or other cutting edge, but rather a single dental pick, like the one shown below. Sara had, in a little less than an hour, taken a tool dental hygienists use to clean your teeth and repurposed it to saw her arm nearly in half.

Sara was promptly admitted to the surgical unit for repair of her wound. Aside from the wound, the initial evaluation revealed no evidence of other active medical illness. Laboratory tests were unremarkable, and her urine drug screen was negative. She was noted to be cooperative but nearly mute during this part of her hospitalization.

After a brief convalescence on the surgical floor, Sara was transferred to the psychiatry unit for psychiatric treatment.

I met Sara the next morning in her room for the initial evaluation. She was sitting upright in her bed, arm thoroughly bandaged. The dressing was intact, with no signs she had been trying to reopen her wound. Some untouched finger food sat on a breakfast tray near her bed (given her presentation, she had a “no utensils” order on admission, as well as a “one-to-one” staff companion, who are assigned to patients at high risk for self-harm on the unit).

Sara was initially hesitant to speak, but the presence of two other women in the room—the social worker and medical student accompanying me—clearly put her at ease. In the first few minutes of the interview, Sara’s behavior confirmed what we had already suspected based on the severity of her injury: she was psychotic. The initial suspicion of psychosis was based on two factors: (1) the family’s report of a period of “depression” preceding an episode of bizarre behavior such as this strongly suggests she had been experiencing the prodromal period of an emerging psychotic illness; and (2) while depressed or severely personality-disordered patients can sometimes inflict grievous wounds on themselves, it is relatively uncommon to see such severe and painful self-injury in someone who is not psychotic (or under the influence of alcohol or certain drugs). To these initial suspicions was added Sara’s current presentation. She was unable to make eye contact. She paused in conversation at unusual times, as if listening to someone speaking whom we couldn’t hear. Her gaze darted around the room and to the ceiling, scanning for threats. She had to stop frequently when speaking to prevent herself from tripping over her own words. Sentences might begin on one topic but often end on a totally unrelated topic, without any discernible logical connection between the two.

As the interview progressed and Sara became more comfortable with us, she explained that over the course of the past year she had come to the realization that her entire family was, in fact, not her real family. Her real family, she said, had been replaced by impostors who looked exactly like them in every detail—enough to fool everyone except Sara—and had brought her to America as part of an elaborate celebrity sex-trafficking scheme. Her father was not the electrical engineer he pretended to be, but was in fact the chief pimp of a famous rapper, tasked with trekking the globe in search of young girls ripe for kidnapping.

Sara’s gradual piecing-together of this conspiracy coincided with her isolating to her room in order to avoid being “shipped off to [famous rapper’s] rape dungeon”. This is a good example of how psychotic delusions are impervious to logical argument and are, as Karl Jaspers said, fundamentally “un-understandable”. Despite fearing she had been kidnapped from her native Nigeria and taken to the American midwest by an elite team of international impersonators/human traffickers, Sara found that sitting alone in her bedroom with the door closed was apparently a sufficient defense against these criminals.

When we asked Sara why she had hurt her arm, she told us she had urgently needed to remove a tracking device that had been implanted by her impostor family when she was asleep. Their taking her to the community mental health center was, in her mind, the final step in shipping her off to an unimaginably horrible fate. Since the tracking device was essential in making sure she made it to her ultimate destination, it had to be removed by any means necessary if she wanted to have any hope of surviving. While she denied experiencing auditory hallucinations telling her to harm herself, she did experience “receiving the knowledge” of the device’s existence and the necessity of removing it.

Why the dental pick? It seems Sara had bought a dental hygiene set online some weeks ago and had, according to her family, spent a brief but intense few days cleaning her teeth for hours at a time. After that, she appeared to have lost interest in it. No one was certain exactly how Sara ended up with the dental pick at the mental health center, but in retrospect her parents wondered if she pocketed it before the verbal altercation at home, perhaps initially as a means to defend herself against abduction. Sara’s ad hoc explanation to me was that if she had used a blade to cut herself, that would have (somehow) interfered with the technology of the tracking device which would have (somehow) harmed her even more. Thus, a pick was needed.

When I asked Sara if she had found the device she was looking for, she said she realized it had been secretly removed a few days ago because the conspirators knew she was going to try to remove it. She wasn’t sure where it was now, but she suspected it might still be inside her.

By the end of our conversation, Sara agreed to try an antipsychotic medicine. Informed consent is not always straightforward in these situations, since it wouldn’t go over very well if I ask her, “would you like a medication to treat your psychotic paranoid delusions?” Instead, we try our best to chart a path that is both truthful and which gets the patient the medicine she needs, even if she doesn’t know she needs it right now. To do this, we leveraged Sara’s paralyzing fears of abduction, troubled sleep due to the paranoia, and inadequate nutrition due to fears of being drugged at any moment. I explained that the medication I was recommending—in this case risperidone—would help her sleep, reduce anxiety, increase her appetite, and generally help her organize her thoughts better.

Between days two and four on the medicine, Sara became progressively less socially anxious. She started attending groups with other patients on the unit (group therapy, aerobics, art therapy, etc.). Her sleep and appetite normalized. In conversation she appeared more engaged, and started making eye contact. Aside from transient fatigue during the first few days, her only notable side effect was constipation (very common) which was resolved with a scoop of polyethylene glycol (Miralax) every 1-2 days as needed.

Day by day, her paranoia decreased. As is common for those with chronic psychotic disorders (eg. schizophrenia) Sara didn’t disavow her paranoid delusions wholesale, rather they became progressively less salient in her mind to the point that she would reference the once imminent conspiracy as if it were some barely-remembered, innocuous inconvenience (“oh, that? I just don’t think about it anymore, it doesn’t really bother me right now…”).

After two weeks, Sara had improved substantially. She was able to care for her daily needs, including her wound. She did not experience any acute resurgence of psychotic symptoms after starting medicine, especially a desire to continue searching for the still-missing tracker. She was able to talk with her family, no longer convinced they were impostors hired to sell her into sex slavery. Although Sara came to understand she was experiencing something unusual, she wasn’t able to fully appreciate the fact that she was suffering from a brain illness (schizophrenia) which was the ultimate source of her distorted perceptions and failure to function normally.

Physically, Sara slowly started regaining movement in her fingers and showing progressively increasing strength in her hand muscles. She had avoided severing the three major nerves entering the hand from the arm (ulnar, median, and radial) likely because she was using a sharp pick and not a blade.

Sara was discharged to the care of her parents a little over two weeks after admission to the unit. During her hospitalization, we frequently met with her parents to educate and coach them on how to care for Sara during her ongoing recovery, as well as planning relapse prevention strategies. She attended our hospital’s intensive outpatient program Monday-Friday for the month after discharge, after which she transferred care to a psychiatric clinic closer to home.

Roughly six months after discharge, I received a note from Sara’s family thanking us for our help. They said her recovery was going well, that she had come to terms with her diagnosis, and was engaged in treatment. They added that she had recently enrolled in a local art school after discovering a newfound passion for painting.

Some Teaching Points:

Schizophrenia often has a prodromal phase preceding the first episode of psychosis. This prodrome typically lasts between a few months to a year, sometimes longer. It is most often characterized by the emergence of “negative symptoms” such as social withdrawal, feeling depressed or empty, lack of motivation, and declining hygiene. This often leads to the prodrome being mistaken for major depression or another non-psychotic illness. People may also start experiencing cognitive problems related to schizophrenia, eg. finding it more difficult to do mentally demanding tasks, or process social cues. With careful attention, it may be possible to detect subtle, sub-threshold “positive symptoms” of emerging schizophrenia during the prodrome. In full-on psychosis, positive symptoms are hallucinations, delusions, and disorganized speech and behavior. During the prodrome, before the first break, one might get the feeling that “there’s a lot of strange coincidences going on lately”, and start “connecting the dots” between otherwise unrelated and innocuous events (think of a milder version of John Nash in A Beautiful Mind, standing in front of a wall tacked with papers, with lines drawn all over making connections between things). A simmering paranoia may develop as well, contributing to one’s already increasing isolation. Communication deficits such as frequently losing trains of thought, use of neologisms, and difficulty keeping one’s thoughts organized may become more noticeable. Correctly identifying prodromal schizophrenia is difficult because (1) as stated above, it is easily misdiagnosed as depression, and (2) not all prodromal cases progress to a full diagnosis of schizophrenia. If prodromal schizophrenia is suspected, early evaluation and intervention is strongly advised.

Patients who have only had a brief triage evaluation by a nurse or social worker in a community setting which lacks hospital resources should not be left alone and unattended for extended periods of time. Brief rounding/check-ins on such patients should occur closer to every 15 minutes, give or take.

While invasive body searches are usually inappropriate and unnecessary in these settings, patients should be encouraged to hand over any potentially dangerous objects. Checking pockets and bags may be appropriate depending on the situation, especially if there is a concern someone is smuggling in drugs or a weapon into the facility.

Whenever a patient has an unusually brutal self-injury that is significantly more damaging than more common forms—such as superficial cutting or burning—psychosis should at least be considered on the differential.

Psychotic patients who self-injure are at high risk of re-injuring themselves, either by trying to remove sutures and reopen the original wound, or by creating a new one. The risk can remain high even when hospitalized and receiving treatment, therefore vigilance is warranted.

People suffering from psychotic delusions can’t typically be argued out of their delusions. For family/friends we recommend neither endorsing someone’s delusions (perhaps out of a desire to stay on their good side) nor arguing against them (which will only risk you becoming the object of the person’s paranoia). Instead, I advocate avoiding a conflict over the substance of the delusion and emphasizing that you’re here to support them and are a safe presence who can be trusted.

Command auditory hallucinations, i.e. hearing voices telling you to do something, should be considered a psychiatric emergency if the content of the command is violent or could otherwise cause imminent harm. For example: “Your roommates are trying to poison you, so you must defend yourself”; “You’re worthless, go walk into traffic”; “Remove the chip they implanted in your stomach”. If the person suffering the hallucinations is willing, they should be brought to an ER. If they are unwilling, EMS may need to be called.

Violence in the context of psychosis can be difficult to predict, despite some of the warning signs discussed above. Those suffering from psychosis can sometimes harm themselves or others seemingly out of nowhere. Sometimes paranoid fears reach such an intensity that they feel compelled to strike out in what they see as self-defense. But, sometimes their actions are just as inexplicable to them as they are to the rest of us.

GRAPHIC PHOTO BELOW

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

The following photograph is from an already-published medical text, regarding a different case (source in the caption). This photo depicts a wound very similar to the one Sara inflicted on herself, except Sara’s wound extended even further up her forearm to the elbow, and was quite a bit bloodier.

Support the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI)— https://www.nami.org/

Dr. Greenwald, thank you for this very educational piece and reminder about the seriousness of this illness.

Can schizophrenia deaden sensations of pain? I can't believe a person able to feel pain normally could do that to themselves.