This piece was originally published here on Sensible Medicine.

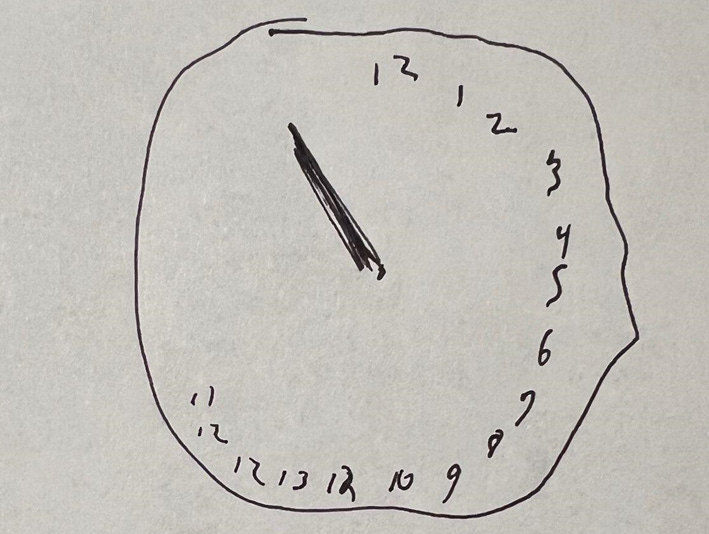

“Here is a pen and paper. Please draw me a clock with all the numbers in place and set the time to ten minutes past eleven.” I handed my pen to “Annie,”[1] and set and blank paper down on her lunch tray. She was a slim brunette around twenty-five years old, draped in a hospital gown. After a pause she took the pen without looking at me, holding it tightly, staring, gaze fixed, at the paper. It wasn’t clear if she had heard me or even registered the instruction. A few more moments passed. A thought occurred to me—had she not blinked once since I walked in? I repeated the prompt and guided her hand toward the tray. She resisted at first, muscles rigid, but gradually allowed me to move her hand to the page.[2] She slowly directed her attention toward the task, put pen to paper and began work on her clock:

After ten or so go-arounds and a few ineffectual “Alright now’s,” I gingerly took the pen from her still rotating hand.[3]

“Al…alright n…S…Sorry, I…”[4] She stuttered haltingly as her hand slowed its rotation and came to rest on the lunch tray, gripping the corner of the paper tightly. She trailed off, staring at the far wall, sitting motionless and tense. I gathered my things, pried the paper from her grasp, and went to find her nurse to quickly administer lorazepam for her catatonia.

An hour or so later I returned to Annie’s room. I greeted her and she gave a nod in recognition. She looked a bit more at ease, with less of a “deer-in-the-headlights” look about her. She was still sitting in her bed but now slowly chewing a chicken tender. I apologized for interrupting her lunch (again) and reintroduced her to the clock drawing task (she had vaguely remembered drawing something before but couldn’t be sure). Her second attempt:

I left again—I’m pretty sure she was still ruminating on the same bite of chicken she was during my first visit—and started Annie on scheduled doses of lorazepam every few hours, planning to return the following day for one more clock. Given the improvement from the first to the second, I was excited to see what a third try would yield.

The next morning when I opened the door to her room, she looked up at me and spontaneously acknowledged my presence—a sign of further improvement. My entrance was timely, as she had received her lorazepam within the hour and so was at her most alert for clock number three:

I congratulated her on her improved clock, although she was less happy with her progress than I was. Shifts changed and I never saw Annie again, although I heard that she continued to recover. I always wanted to ask her what it felt like when she was drawing those clocks. I have treated other patients with catatonia and have since always asked them, once recovered, what the experience was like. Some don’t remember, but others say it is something like “all-consuming, ever-present fear.”

I saved her clocks, as I have the writings, drawings, and assorted scribblings of many of my other patients. Many are educational and are in steady rotation for showing to students and residents. Others are disquieting memorabilia, records of suffering and triumph, artifacts of minds plunged into nearly unimaginable torment and then struggling to crawl back into the light. Often, these artifacts communicate when they could not. They transport me back to an encounter with a particular human being who is facing misfortunes the likes of which I am thankful I have not yet known.

Good physicians reflect regularly on their patient encounters, but usually only the most vivid memories really retain their color and life (and ability to instruct). A few get stored away to be dispensed as wisdom to a junior colleague. But many of our anecdotes, touching moments, and clinical pearls get washed away in the churn of a busy day, lost forever.

I was inspired to save Annie’s drawings in part because of the prompting of my colleagues who had researched performance on the clock drawing task in catatonia and had worked towards developing its further clinical use. The similarity between different patients’ clocks is at times striking, with some taking on the appearance of “a Dali-eque image, as if the numbers are dripping off the weeping clock like tears”[5] (see image 2 above). And, as the catatonia is treated, the clocks gradually assume a more recognizable form—a record of real time recovery from a potentially catastrophic illness.

At first, I collected only clocks; later I expanded my collection to any of my patients’ writings or drawings with which they were willing to part. I find, a wealth of insight—often beautiful, just as often chilling—into my patients’ lives. It is not uncommon to ask for a sketch from a patient on rounds only to find a full portfolio waiting for me the next day. Now, I make a point to request pieces from any patient with the inclination to make them, and I recommend this practice to any physician reading this, psychiatrist or otherwise. After all, the resourceful physician never misses an opportunity to connect with and understand his patient: why then should we limit ourselves to the spoken word?

Martin Greenwald, M.D.

[1] Patient names and other identifying information have been altered to preserve confidentiality.

[2] Waxy flexibility

[3] Perseveration

[4] Echolalia

[5] Credit to Michel Medina, MD, for this phrase.

This is an absolute must do now for anyone treating Catatonia. Thank you for this.

Doc,

Thanks for these posts - very much appreciated.

Question: how does a benzo make a cataonic patient more alert? I would imagine any GABAergic depressant would have the opposite effect.