This piece was originally published here on Sensible Medicine.

In my previous Tidbits post, I focused on the use of patient writings and drawings in psychiatric care. That post focused on one case of catatonia, and how the clock-drawing task can yield useful diagnostic information and evidence of treatment response.

There is great value in asking your patient to write something—anything—for you, without any immediate clinical end in mind. For those familiar with serious mental illness, your patient’s written work can add significant depth and richness to the treatment, opening new avenues of communication that spoken conversation cannot fully capture. Sometimes it serves as a prompt for an important discussion that is difficult to bring up directly; other times it may just let them know you’re interested in them as a person.

When the patient allows, I save these documents and rummage through them with some regularity, inevitably noticing a new detail, or recalling something about them I had forgotten. Below are selections from five different patients, all of them treated on an inpatient psychiatric unit. The first four suffered from psychotic disorders—two with bipolar disorder and two with schizophrenia—and the fifth from severe alcoholism and early dementia. Each of their works are closely connected to specific memories I have of their treatment, but they can also be appreciated for their own sake, I think, as glimpses into strange and fearful states of mind that are felt by so many but so rarely talked about.

Maria

“Maria”, a 21-year-old woman with bipolar disorder, was hospitalized for mania. Her older brother had schizophrenia, and psychotic disorders ran on the mother’s side. When her mania was resolving, I asked her to draw me a picture of her childhood:

Maria offered me this drawing the following day, again on the theme of her brother’s illness. She had drawn it after a group therapy session focused on working with what is in our power to change versus what cannot be changed:

Libby

Sometimes writing is all you have. “Libby” was a twenty-year-old woman with schizophrenia. She was so paranoid she would not speak to us, eventually indicating her only method of communication would be in writing due to unspecified legal fears. This is her attempt to give us information to contact her family:

She also wrote about her rationale for refusing psychotropic medication, which she believed was against “the health code” and would result in her personal and financial ruin:

This continued for about a week, but eventually, with her family’s insistence, she agreed to take medication. She improved enough that she was willing to speak to us, and her idiosyncratic hash-marked handwriting started to normalize. Her speech and writing, however, remained stilted and disorganized, evidence of her ongoing thought disorder. Given the severity of her disease, she unfortunately remained significantly impaired when discharged back home.

Richard

“Richard”, a man in his early-30’s with schizophrenia, was hospitalized after three weeks of neither eating nor bathing. Like Libby, he was too paranoid and afraid to speak to anyone on the treatment team. He had brought a notebook from home filled with his writings, however, and after I expressed some interest in it, he turned out to be more willing to show me his written work than talk to me. Much of the notebook was filled with his thoughts on the supposed role he played in some kind of bitcoin conspiracy. The list at the end caught my eye, and helped prompt productive discussion.

Once he started taking medication, his condition improved markedly. We had a number of interesting exchanges about the social function of religion and the meaning of repentance. Most importantly, he avoided any of the “Game Over” options, and was discharged much improved.

Donald

“Donald” was a forty-five-year-old man with alcoholism and early-onset dementia. His family had cut him off some years before and he was totally alone. It was with Donald that I first came to know what truly desperate alcoholism looks like. He looked twenty years older than he was and already had at least one bout of pancreatitis and numerous alcohol-withdrawal seizures under his belt. He had a tremor, impaired balance, and decreasing executive function.

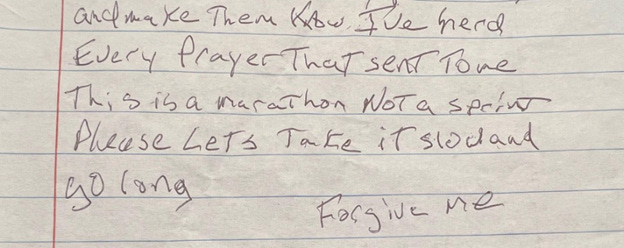

This is the end of a short poem he wrote; the beginning was omitted due to family details he included. He was discharged to a long-term rehab facility. His tremor was still resolving when he wrote this:

Trisha

“Trisha”, a nineteen-year-old woman with bipolar disorder, was in the third trimester of her first pregnancy when she developed severe mania. She was hospitalized when she could no longer safely care for herself. One morning I walked into her room and she was holding this paper up against her window, facing an empty, locked, courtyard. She was desperate to escape, first, because her delusions told her that we were the police plotting to take her to prison in order to force her to get an abortion, and second, for the much more sensible reason that neither she nor any other patients were allowed outside while hospitalized. At one point she asked me a question that many patients have subsequently asked in various ways: “How do you think any of us are going to get better without going outside? Haven’t y’all ever heard of getting some fresh air?”

She has a point, doesn’t she? Of the psychiatric hospitals I have been to, I can think of very few that allow patients to go outdoors with any regularity, and many cannot accommodate it at all.

Martin Greenwald, M.D.

I found some of my patients with a bipolar disorder could often write reams and reams of material, the other issue I found with many of the patients I have known over the years was often a strong artistic talent, often depending on their degree of wellness. I honestly loved psychiatric nursing, I believe I was good at it, I found it incredibly rewarding-if I was prepared to be patient, kind, and wait for even small steps forward towards health.

I love reading this stuff! Even though I have been everywhere in my time on Earth, my exposure to people with schizophrenia has been quite limited. Nevertheless, I find this horrible condition fascinating.