I'm working on writing briefer posts, and since I can't write only about psychiatry without going crazy, I’m dipping back into philosophy (the next Psychiatric Evaluation piece will be up next). This will be less polished, as I’m trying to shake off some counterproductive perfectionism.

Recently, I had a nice exchange with a philosophy undergrad on Astral Codex Ten, discussing opinions on philosophers people admire or dismiss, and why. I’ve also seen a few post around Substack on the theme of “what makes for good/bad philosophy”. So, I thought I’d share a few thoughts on what makes for enjoyable and rewarding philosophy (if not “good”).

I claim no perfection here—I'm an aspiring philosopher too. A lot of this is a reminder to myself, but if it helps anyone else, I’m glad.

In philosophy: Read widely, and don’t limit yourself to one tradition or school. Read the actual books, not just commentaries—you’ll have a vastly different experience reading Plato than reading about him.

In general: study broadly outside philosophy. This includes literature (consider reading a few novels with philosophers in them). The more educated you are, the better. This also means reading old books, a habit which has many virtues, among them being inoculations against our tendency toward presentism, cultural amnesia, and idea recycling. Most (but not all) new ideas are nothing of the sort (which is ok).

It’s fine to obsess over certain problems, but beware of becoming a philosophical scholar instead of a philosopher.

When you're convinced a philosopher or idea is wrong—especially on something you care about—read them more thoroughly than those you agree with. You'll either be converted to their truth faster, or you’ll learn from their errors.

Get acquainted with relevant adjacent fields, eg. if you spend all day thinking about philosophy of mind, you might consider learning something about neuroscience.

Learn a few practical or hands-on skills, if not as training for a backup profession, then at least as a hobby. And if you think you can’t do philosophy while gardening or welding or cooking, you’re missing the point.

Most philosophical errors don’t come from a lack of intelligence, but from: (1) lack of courage to follow an argument to its odd or unpalatable conclusion; (2) mistaking personal intuition or worldview for universal truth; (3) confusing words and concepts for the reality they represent; and (4) fear of death.

Doing productive philosophy requires some combination of time alone and time with others. Rare is the person who can philosophize well either in total isolation or in constant company. Try to find the balance that works for you, and if you have a preference for the one, be sure not to neglect the other. Just because you love finding the truth by one means does not imply that the truth desires to be found by you in that particular way.

Always be ready to assimilate a bit of anything you encounter. Cultivate the openness of a poet and don’t disdain any avenue of learning—even the alleys and byways. Dharma gates are everywhere.

It’s easy to forget that philosophy has always been subversive to the political order, and because of its very nature will remain so.

Something we must all come to realize in our own way: that the simplest things— and these are also the highest and greatest things—cannot be articulated, but can at best be approximated or intimated. Wisdom is, ultimately, silent. The tiniest and greatest converge in their ineffability. Yet it is precisely in that necessary silence that philosophy begins, and ultimately ends.

Practice seeing familiar things as if for the first time.

Never fool yourself—especially mid-argument—into thinking you are motivated solely by a desire to find the truth.

You can’t always think what you think you can think! Just because you imagine you can “conceive” of something doesn’t mean you can actually do it. Introspection is deceptive and unreliable. The belief that our mind is transparent to itself is a constant tripwire. Looking inward generates as many illusions as looking outward, if not more.

There are always fads—even in philosophy—and you are never as immune to them as you think you are.

Concepts can mislead and blind us just as much as they can illuminate.

Familiarity with Indian and East Asian philosophy will enrich and deepen your engagement with the Western tradition.

It is a mistake to think philosophy is something that occurs primarily in your head.

Two crucial ingredients: flexibility and the capacity to be continually astonished by the ordinary.

Philosophy is one of those things where it is healthy and normal to ask yourself periodically, “what the hell am I even doing?” Whatever your goals are in philosophy, presumably one of them involves not being on your deathbed regretting the whole affair.

Pay attention.

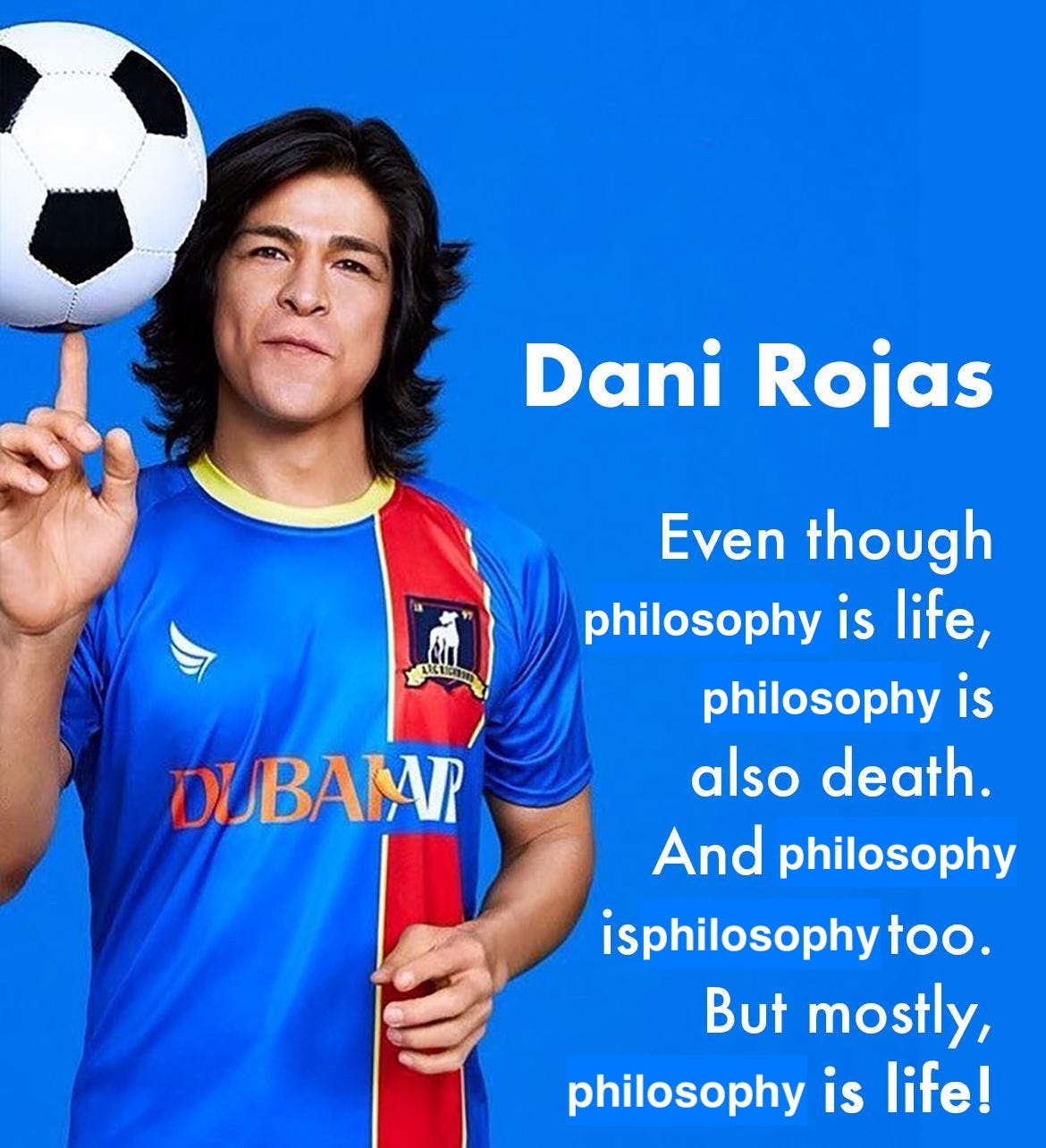

Philosophy is not ultimately contained within books; philosophy is about life. But however you want to define it, if you don’t allow it to become a part of you, if it doesn’t make you a better person—in the real-world, not just in your utopian mind-palace—then you’re still missing the fundamental point.

Be humble. Remember, your predecessors may not have been right about everything, but they weren’t stupid. Dismissing something as “bad philosophy” is usually an excuse not to engage with it.

If you think you’ve finally figured it all out, you haven’t. The only thing we should be really certain of is that we are still, and always, learning.

Banger post

By nature I’m not an introspective person, but have interest in philosophy as it can lead to exploration of different ways to understand the world. But, for me, this is key; understanding the world is of greater consequence than dwelling on myself. I’m convinced by the mental health epidemic we see today that as soon as I make this world all about me, the more miserable I’ll become.