The Psychiatric Evaluation for Non-Psychiatrists, pt. 2

The Mental Status Exam

Part 1 of the series introduced the psychiatric evaluation and the mental status exam (MSE). As a reminder, the format I will be using for the entire psychiatric evaluation is:

Components of the Psychiatric Evaluation:

1. Psychiatric Interview

a) Chief Complaint

b) History of Present Illness

c) Past Psychiatric History

d) Substance Use History

e) Developmental and Social History

f) Medical/Surgical History

g) Family Psychiatric/Medical History

h) Review of Systems

2. Exam

a) Mental Status Exam

b) Cognitive Exam

c) Physical & Neurologic Exam

3. Collateral Information

4. Diagnostic Tests/Procedures

5. Assessment/Formulation and Treatment PlanFor part 2, we’re going through the MSE: a systematic method for describing all the relevant observable characteristics of a patient, as well as making inferences about the patient’s mental state from the observed phenomena, at the time of the evaluation. It begins when I meet the patient, occurs continuously throughout the interview, and ends when we part ways. Although I ask certain questions directly—about mood for example—most of the mental status exam is either observed or naturally elicited from the patient and is not a step-by-step exam in the traditional sense.

The MSE and the rest of the psychiatric history are the two critical elements of the psychiatric interview. The history provides the patient’s subjective narrative of events, while the exam provides some objective facts of the current situation. When the history and exam are consistent, we can proceed with a diagnosis and treatment. When they are inconsistent, we can follow up to determine whether the patient’s history is accurate, or if we need to clarify our exam findings.

Again, the exact wording and order of the items on the list varies:

1. Appearance 2. Level of Alertness & Orientation 3. Attitude/Demeanor 4. Behaviors/Motor Activity 5. Speech & Language 6. Mood 7. Affect 8. Thought Process 9. Thought Content 10. Abnormal Perceptions 11. Idiosyncrasies 12. Cognition 13. Insight 14. Judgment

1. Appearance

Your patient’s appearance is typically the first thing you notice, and it is worth attending to closely (Oscar Wilde said that it is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances). Psychiatrists focus so much on what our patients say that we can easily neglect what is plainly in front of our eyes. And while it is usually premature to diagnose based on appearance alone, a patient’s physical appearance can offer valuable clues that either point toward a diagnosis or give important contextual information about their self-presentation and life circumstances.

Here are some of the features I attend to: apparent age (especially if the patient looks significantly different than the stated age), sex, race/ethnicity, body habitus and weight, posture, dysmorphic features, visible signs of illness (e.g. rash), body alterations including piercings and tattoos, injuries, scars, signs of prior medical procedures, dental hygiene and missing teeth, body hygiene and grooming (including hair, makeup, nails). Note signs of drug use such as needle injection marks or tobacco stains on fingernails. Don’t overlook signs of self-injury, such as cutting or burning, and whether the wounds are recent or old. Observe manner of dressing: clean vs. dirty, appropriateness to the occasion including both formality as well as accommodating the weather, sloppy vs fastidious, any accessories, eccentricities, notable logos or insignias. Body odor and other smells are typically included under appearance. Depending on the context, I note the position and activity of the patient as I arrive, e.g. lying in a hospital bed, sitting in a chair, standing in the waiting room, etc.

Naturally, when observing someone’s appearance you’re also observing their level of alertness, behaviors, and attitude, which are described in separate sections. The beginner’s error is to anguish over the technicalities of the MSE structure, e.g. whether you should comment on posture as part of the “Appearance” or “Behavior” section, instead of noticing whatever is important about the patient’s posture in the first place.

Vignette:

(For all vignettes, I’ve made necessary adjustments to preserve patient anonymity, as always).

Mr. B is a 44-year-old caucasian man with unknown medical/psychiatric history presenting to the ED in police custody after attacking his neighbor during a verbal dispute. He is sitting up on the hospital bed, two officers standing watch. I ask the officers to leave the room while I interview him.

Mr. B is approximately 5’8” with a normal weight and body habitus. His hair is thinning and cut short. His wrinkled, aged face makes him look closer to 55 or 60. He has two missing teeth and many others are crooked. His breath is pungent, but his body appears reasonably clean. He is wearing a sweat-stained white tank top and worn blue jeans, which is appropriate for the spring weather. In contrast to his clothing and overall appearance, his flat brim Chicago White Sox baseball cap sitting on the bed is nearly spotless. He has half a dozen small tattoos on his chest, neck, and back that are difficult to make out. On his left arm is a tattoo of a flower with birth-and-death dates about 30 years apart printed beneath it, presumably to remember a deceased friend or relative. On his upper chest is a tattoo that reads “Mercy”, and on the lateral side of his right arm, just above the elbow, another that in elegant cursive reads, “Fuck”.

When I’m going to see a patient, I typically think about appearance as falling into four broad categories. This is just a loose heuristic for organizing my thinking, not some method of objective categorization. The overriding priority is to notice first, categorize second.

Things that need to be dealt with right away. This includes obvious things like walking into the patient’s room and seeing that they are in the middle of a medical emergency or otherwise appear acutely unwell.

Things the patient either can’t control or can’t control easily, such as sex, ethnicity, signs of longstanding illness, birth defects, body type, etc.

Aspects of appearance the patient usually can control, such as clothing, jewelry, hair dyed various colors, signs of self-injury in certain cases, or tattoos that say “Fuck”. These aspects of appearance may be means by which patient communicates something about themselves to the world (as was the case with Mr. B, who, it later became clear, had antisocial personality).

Aspects of appearance relating to either habit, circumstance, or present illness. This usually falls somewhere between what the patient can’t control (2) and can (3). It includes things like poor hygiene due to homelessness and chronic psychosis, which isn’t really involuntary in the sense of (2) nor is the patient making a statement about himself as one would with a body piercing like in (3). It would also include the peeling, red hands of the patient with OCD who has bleached them dozens of times per day, poor hygiene due to recent onset depression, bald spots and thin eyebrows on a person with trichotillomania, or garish makeup on a woman in a manic state.

2. Level of Alertness & Orientation

One of the first things we notice about a patient aside from the aforementioned aspects of appearance is whether she is conscious. Closely related to assessing level of consciousness is determining whether or not she is delirious, demented, or otherwise cognitively impaired. This section could be considered the first part of the cognitive exam.

The syndrome of delirium is a large and complicated topic, but at the most basic level it can be thought of as a kind of acute 'brain failure' analogous to heart or kidney failure, where the organ experiences a sudden global impairment in function. In the case of the brain this typically results in disorientation with regards to space and time, inability to maintain attention, fluctuating awareness, memory impairment, hallucinations, and motor agitation or retardation. From the diagnostic perspective, it is important to distinguish delirium from psychotic disorders and dementia, as well as to find its source and treat it if possible.

Delirium is especially common in medically compromised or otherwise fragile patients and is never a good prognostic sign. This is one reason it is important to recognize and address quickly. The differential diagnosis for underlying causes is long: infection, medication/drug ingestion or withdrawal, metabolic abnormalities, stroke, encephalitis, catatonia, dehydration, liver failure, and so on.

The most basic way to assess whether a patient is “oriented”, aside from observing her overall behavior in the interview, is to ask the year, month, day, date, and her current location/situation. In cases where the patient is obviously cogent these questions may not be necessary. In cases where we suspect impairment, further examination is indicated.

3. Attitude & Demeanor

The line between attitude/demeanor and behavior isn’t always clear, but for this section we’re focusing on how the patient intentionally comports herself during the interview.

One of the first things we do when seeing a patient—especially a hospitalized patient—is to determine whether the situation is dangerous, either for ourselves or the patient. Sometimes a violent encounter erupts unpredictably, but very often there are warning signs for observant clinicians to notice and act on before it gets to that point. One must always observe for signs of agitation or potentially threatening behavior such as clenched fists, scanning the exits, tone of voice, violent language or threats, menacing eye contact, increased fidgeting, pacing, etc. All trainees are taught to keep themselves between the patient and the exit in cases where violence is a possibility. Neckties and other accessories/jewelry that can easily be grabbed should not be worn on an inpatient psychiatric unit.

General observations on attitude/demeanor include: degree of eye contact or lack thereof, whether she shakes your hand, her degree of overall cooperativeness vs hostility, courtesy or rudeness, acting guarded or showing suspiciousness, as well as other attitudes such as arrogance, aloofness, over-formality, over-familiarity, seductiveness, dominance, helplessness, ambivalence, puzzlement, manipulativeness, and so on. Posture could be included here or under behaviors, below. It if were indicative of the patient’s attitude toward me, e.g. an aggressive posture, I would include it here; a rigid posture due to Parkinson’s disease, on the other hand, would go in the motor activity section.

The patient’s attitude at the beginning of the appointment can be particularly illuminating: How does she greet you, if at all? Is she in the waiting room attentively waiting for her appointment? Does she hold up her hand and tell you to wait while she finishes up a phone call? Watch for sudden and unexpected changes in attitude throughout the interview, especially negative ones.

Vignette:

Intern year. I walk into the ER after being paged to see a 79-year-old African American woman who was brought in by her family due to paranoia and agitation at home. They suspected she was using cocaine. I knock and peek into her room. She’s sitting up in bed, her wire-thin frame draped in a hospital gown. Her face is small and heavily wrinkled, with a hairstyle bearing an uncanny resemblance to early 1980’s Don King. She’s talking to a family member who has accompanied her.

“Hello, Ms. C, my name is Dr. Greenwald, I’m with psychiatry. May I come in?”

She doesn’t reply immediately and only slowly turns to meet my gaze. Her facial expression is one of thinly veiled annoyance bordering on disgust. She gives me a once-over, staring with eyes narrowing to a squint. Then, with a stern, calm voice full of ice-cold contempt replies, “Get out of my room you limp-dick motherfucker.”

Some aspects of a patient’s demeanor can point towards a diagnosis, but just as important as diagnosis is being able to work with the patient in the first place. The idea is not to observe that the patient’s attitude is “hostile” (or whatever it is) and then continue on to the next checkbox, but to start to understand whatever is causing this presentation and determine how best to work with it.

Patients can have a less-than positive attitude for all kinds of reasons. Maybe they’re sick, or sleep deprived, or in pain, or all of the above. Sometimes they assume an aggressive or oppositional stance in an effort to establish their independence and autonomy. This is especially common for those who view going to the doctor as infantilizing. Understanding these factors and addressing them early will make subsequent treatment much easier because it’s worth putting thought into how you’re going to work with an adversarial or “difficult” patient. I’m confident that many “difficult” patients either stop being difficult or become far less difficult once we really take the time to understand where they’re coming from, what they want, and why they’re in distress.

In the case of Ms. C, my priority was just getting through the door. I had good reason to suspect drugs had something to do with her attitude, but that may not have been the whole story. What kinds of family conflict are going on? Some underlying psychiatric condition? A deep distrust of doctors? In her case I defused the situation with a bit of humor and assertiveness, telling her that I was flattered and that while the pleasure was all mine, I really must speak with her for a few moments. To my surprise, she agreed without further argument or personal attacks. The rest of the interview was still rocky, but getting through the door ended up being most of the battle.

4. Behaviors and Motor Activity

Here we observe for any abnormalities in gait, posture, or movements. Noticing and accurately evaluating motor abnormalities can be invaluable in diagnosing a wide range of neurologic and psychiatric illness, as well as medication side effects. A few of the general observations include the degree of overall movement (e.g. slowed, agitated), whether voluntary vs involuntary, continuous or intermittent, regular vs irregular, and what parts of the body are moving. We look for asymmetries in movement and posture, as well as signs of muscle weakness. We observe for the presence of tics, as well as rituals or compulsions such as counting, checking, skin picking, hair pulling, and hand wringing. We note any tremors or dystonia (increased muscle tone) which could indicate neurological illness or medication side effects. And we can’t forget signs of catatonia like stereotyped movements, maintaining odd postures, and repeating the examiner’s movements or speech back to him (echopraxia and echolalia).

We observe the patient’s gait: a hunched posture with short, shuffling steps might indicate Parkinsonism; poor balance might be due to loss of proprioception in the feet due to diabetes.

Patients who are actively hallucinating may appear to respond to voices or other stimuli that aren’t there. I included a separate section for abnormal perceptions, but responding to internal stimuli could also be included here.

Vignette:

Mr D. is a 29-year-old man presenting to clinic for a second opinion evaluation for six months of worsening anxiety. I note that he is tapping both his feet and wringing his hands throughout the interview. We review his medications. He reports trials of fluoxetine (Prozac), sertraline (Zoloft), and escitalopram (Lexapro) with minimal success. Three months ago he was prescribed aripiprazole (Abilify), and the dose was increased to 20 mg/day last month. When I ask about his fidgeting, he reports always being fidgety but with significant worsening in the past few months. He reports that his nurse practitioner told him the fidgeting was a symptom of anxiety and increased the aripiprazole dose further.

On further questioning, the fidgeting clearly worsened shortly after starting the aripiprazole, and I suggested it may be a side effect called “akathisia”, a continuous and extraordinarily uncomfortable need to move (think restless leg syndrome on steroids). I advised he stop the offending medication and prescribed him propranolol and a benzodiazepine for symptomatic relief while it abated. He returned for a follow up one week later and the akathisia had almost entirely resolved.

5. Speech & Language

This covers the verbal production of speech. The meaning of the speech is commented on either in the thought process or thought content sections.

Speech abnormalities—sometimes subtle, sometimes unmistakable—are ubiquitous in psychiatry. Aspects of speech we consider include: how much the patient talks (quantity), how fast (rate), volume, articulation and fluency, prosody, rhythm, latency time of response, and paraphasic errors (unintended syllables, words, or phrases in speech). We note unusual speech patterns such as vocal tics, punning, rhyming, and neologisms.

Vignette:

Mr. J is a 23-year-old man with schizophrenia hospitalized due to worsening paranoid psychosis. He appears guarded and suspicious of us. I introduce myself and ask him how he’s feeling today.

“That may be possible at some point in time, but I’m afraid that in this particular scenario…situation, that specific information is not something I’m…authorized…to divulge, presently, publicly, given the circumstances. Confidentiality protocols and such, you understand.”

In the case above, the patient is exhibiting what is known as stilted speech, in which someone speaks in an inappropriately formal way. It is often difficult to follow and may appear overly philosophical or legalistic. It is often seen in schizophrenia as well as autism.

People who are manic tend to have abnormal speech, as in Mr. A in part 1. When speaking about his being the resurrected Anne Frank he spoke so quickly and forcefully that he couldn’t be interrupted, which is called pressured speech. He was very loud, and used frequent alliteration and would occasionally rhyme or sing instead of speaking.

Other speech abnormalities one might note include: verbal compulsions due to OCD, a wavering voice due to anxiety, slurring due to intoxication, or hypophonia due to Parkinson’s disease.

6. Mood

Here we record the patient’s stated mood. A simple “How would you describe your mood now/lately?” works well. This is in contract to affect, which is how the patient looks like they feel. Typically mood is recorded as a quote of the patient’s response to the question.

We note the content of the answer itself and especially whether the stated mood is incongruous with the patient’s affect. This can give insight into how well the patient understands his or her own emotional state. Alexithymia is a term that describes difficulty or inability to recognize and understand one’s own emotions. This may be seen in Autism, for example, as well as some personality disorders.

Sometimes a generic answer like “OK” means they actually do feel “normal”, but might also be a means of not actually answering the question. If I suspect this is the case, I prod further (one things many learners need to be taught is that psychiatry is an invasive field, and it’s ok to push your patients to discuss difficult things—that’s why they’re here and why we trained to do this job).

Tracking patient’s moods is one of many ways we look at progress. When the depressed patient starts saying they feel better day by day, or the manic patient stops saying he’s so happy that the light of The Radiant Spirit is going to burst through his chest, we’re making progress. These observations are ideally consistent with the patient’s observable improvement in other areas, such as the depressed patient getting up to engage with others more, or the manic patient sleeping better.

Some examples of moods I’ve heard recently:

“Fine”; “Good”; “OK”; “I don’t know”; “Depressed”; “Worthless”; “Anxious”; “Nothing”; “I think I’m dead”; “Empty”; “A little worse than you look”; “a burden”; “Never been better”; “Like I want to hurt someone”; “What kind of question is that?”; “I’m on top of the world, baby”; “Amazing”; “That’s personal”.

7. Affect

In contrast to mood, affect describes observable behaviors such as facial expression and gestures that indicate a particular emotional state. Affect naturally includes elements from other areas, e.g. an angry tone of voice along with the angry facial expression.

The quality of the affect is often described as euthymic, dysphoric, elated, expansive, irritable, anxious, and so on. A euthymic affect is one that is in a fairly normal range without appearances of significant emotional disturbance, i.e. “normal face”.

We observe the range of affective expression—does the patient’s affect respond appropriately to the situation—and whether it appears normal, labile, or constricted. We also observe the intensity of the affect, e.g. mildly anxious vs panicked, upbeat vs elated. We look for shallowness and superficiality in affect, along with artificial intensity.

Vignette:

Ms. H is a 28-year-old woman with a history of bipolar disorder admitted to the psychiatric unit 9 days after the uncomplicated delivery of her first child. Her husband reported her mental state rapidly declined after multiple days of poor sleep with their newborn. He brought her to the hospital after finding her pacing aimlessly around their house in the middle of the night.

On entering her room we see her in her hospital gown seated on the floor cross legged. Nursing reported she has been in various seated positions on the floor for most of the morning and refuses repositioning or help getting up. She stares off at the wall, occasionally moving her hands slowly in front of her face as if trying to swat a fly in slow motion. Her facial expression is unsettling: lips turned slightly down as if frowning, but with facial muscles tensed such that it looks as if she could somehow also start smiling at the same time. Her eyes were wide, and the rest of her facial expression looks somewhere between “petrified” and “in a trance”. Her expression is almost unmoving and at times she appears frozen. At one point during the interview she becomes incontinent of urine but does not appear to recognize it or get up from the floor.

The case above is a particularly striking example of abnormal affect. In this case Ms. H had severe catatonia due to her bipolar disorder (which might be the most common cause of catatonia). Those with catatonia can occasionally have odd or bizarre facial expressions, sometimes maintained for long periods of time. This may go along with rigidity in the rest of the body as well.

In Ms. H’s case we promptly administered electroconvulsive therapy which led to her catatonia resolving just as quickly as it had come on, and there did not appear to be an underlying depressive or manic episode needing further treatment. She was discharged home to her family in just under a week (with close follow-up, of course).1

8. Thought Process

Thought process is a description of how the patient’s thinking progresses through time, as inferred primarily from speech. It can be thought of as the way the thinking flows—as opposed to the contents of the thoughts themselves. Accurately assessing thought process is a fundamental task in the MSE because disturbances in thinking of some sort are prominent in almost all psychiatric conditions.

It’s difficult to give a rigorous definition of normal vs abnormal thought process. Functionally, someone likely has a normal thought process if after speaking with them you can think back and say I understand how their thoughts progressed from A→B→C, etc. This doesn’t mean a normal thought process is “perfectly logical”, rather that it conforms to the typical pattern of human thinking as manifest in speech. (When our minds are wandering, or during daydreaming, our own thought process becomes less coherent as well).

Since Karl Jaspers we’ve been appreciating that for diagnostic purposes the form thinking takes is often more important than the content of what is thought. In the case of delusions, for example, if my patient believes that Denise Richards once brutally attacked her with a scalpel (see next section below), the crucial fact is not that the attacker is Denise Richards instead of Neve Campbell, or that she stabbed her with a scalpel instead of trident, but rather that something in her brain’s “belief-updating-system” is no longer working. What makes her belief a delusion is not that it’s weird or false, but that neither bottom-up external feedback (new sensory input) nor top-down internal feedback (thinking the belief through) can dislodge it. No amount of reasoning or evidence will convince her she is delusional because the cognitive processes that integrate new information to adjust preexisting beliefs are not functioning properly. (That said, the content of what patients are thinking still matters, of course. E.g. it matters if the patient delusionally believes that someone he knows wants to hurt him, since he may then act out of a perceived need for self-defense; or if the patient thinks a chip has been installed in his neck which he needs remove with a sharp object).

Someone’s thought process can become deranged in various ways depending on the underlying cause, so it is important to notice the details and specific character of the disturbance. We observe the speed of thinking and the rate at which new thoughts are generated: is it pathologically rapid, as in mania, or pathologically slowed, as in depression? We note how the patient’s mind moves from one thing to the next and whether there is any logical connection between them. We observe whether he can stay on topic, whether he moves from thought to thought too rapidly, or is unable to move on from a given thought.

For example, circumstantial thinking involves abnormal digressions and elaborations into marginally related subjects before eventually returning to the topic at hand. Tangential thinking refers to the movement from one topic to another unrelated topic, in unexpected fashion, without returning to the original. Those who cannot move on from a topic show perseveration, as in OCD or catatonia.

Disordered thinking (also called psychotic thought process or thought disorder) is one of the primary features of psychosis. Depending on the severity, psychotic patients may have trouble maintaining attention and keeping a coherent line of thought for a sustained period of time. This is why especially in situations of diagnostic uncertainty I recommend letting the patient talk without interruption, which in cases of psychosis will often lead to their manifest inability to maintain the conversation. In serious cases they will become derailed mid-sentence and have difficulty getting out a complete thought, or may talk in word salad, which is so disorganized as to be virtually unintelligible. Words in a stream of thought may become ordered based on sounding similar rather than having any semantic connection, leading to bizarre rhyming and alliteration called clanging or clang associations. Sometimes the psychosis is so severe that patients become mute until the condition is alleviated.

One of the problems with having a thought disorder is that it makes it difficult to think through problems, such as the fact that your brain is currently sick. Those with disordered thinking are frequently either unaware that their faculties are impaired, are in denial about the impairment, or are reluctant to admit the impairment to others. Reluctance to divulge symptoms can sometimes come from other symptoms themselves, such as hallucinatory voices telling the patient not to speak, or paranoid fears that if we find out they’re sick we’ll euthanize them.

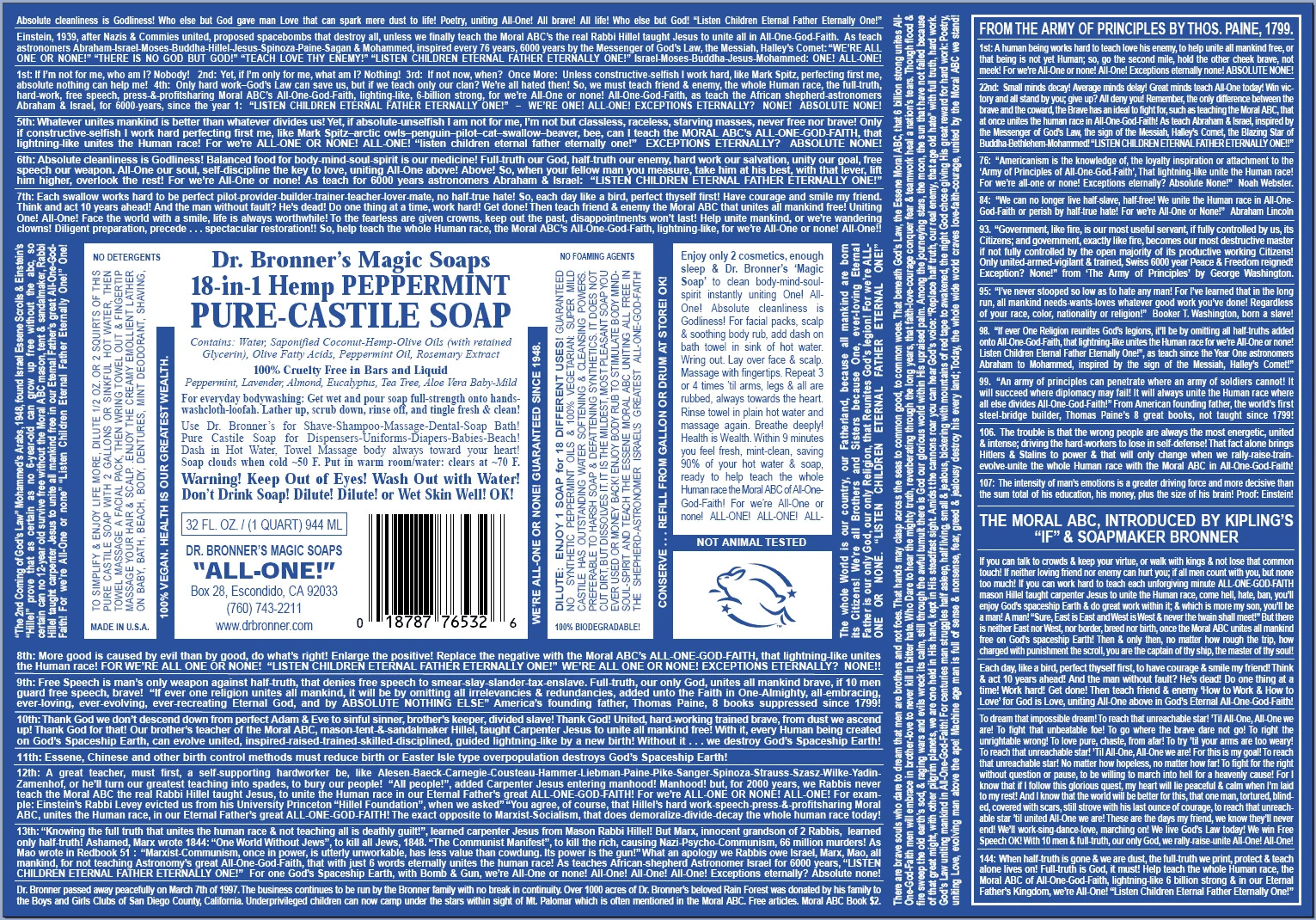

For one of the best illustrations of disordered thought process, consider the Dr. Bronner’s soap label. The picture is worth the probably-more than a thousand words on it. This is the kind of speech I might expect in severe mania. The rapidity of the thinking jumps off the page, and in the MSE we would use descriptors like disorganized or loose associations. Although he returns to certain themes —“The Moral ABCs”, “All-One or None!”—the whole thing is basically an outlandish, directionless exhortation. Notice the numerous clang associations, and the margins jammed with text as if to indicate its uninterruptible quality.

A psychotic thought process is also very difficult to imitate or fake (at least for any sustained period of time). In cases where the patient’s narrative may be unreliable, or if other reported symptoms such as hallucinations are not evident, then the presence or lack of a psychotic thought process can often reveal the fact of the matter. Anyone can say they have hallucinations, and some people are good at appearing like they’re responding to voices in their heads, but very few people in my experience can convincingly talk like they’re psychotic when they aren’t.

9. Thought Content

Thought content describes abnormalities in what the patient is thinking. The most important kinds of pathological thought content includes: suicidal or homicidal ideation, delusions, obsessions, ruminations, and phobias. Many of these can be further sub-categorized. Here I’ll look at suicidal ideation and delusions in more detail.

Suicidality

If a patient is thinking about committing suicide, we want to know. There isn’t much we can do to alter someone’s long-term risk for suicide, and I’m not convinced psychiatric hospitalization has much effect on suicide at the societal level, but we can do a decent job of stabilizing someone if they happen to be brought in right before they do something dangerous. Then the primary goal becomes keeping them safe while hospitalized, which is not always a trivial matter, since suicides on hospital units can happen.

Suicidality exists on a spectrum. On one end is “active suicidal ideation”, which involves the intent and/or plan to kill oneself. At the other end of the spectrum is “passive suicidal ideation”, a wish to die but with no plan or intent to carry it out. And then there all the shades of gray in between. Some clinicians are reluctant to go into too much detail with patients about their suicidal thoughts, perhaps out of a misplaced fear that it will induce the patient to act on it. I have seen no evidence that this is the case. Suicide, like sex, drugs, money, gender, and all those other taboo topics must be approached honestly without fear. Patients can sense when a doctor is asking a question he doesn’t want to ask, and they are often more than happy to remain vague themselves in order to move the conversation along quickly. In contrast, approaching a taboo subject in a frank yet tactful manner usually helps the patient feel more comfortable talking about it openly.

When assessing suicide risk, there are many factors from the patient’s history to take into account such as past attempts, family history of suicide, age/sex, marital status, children, alcohol and drug use, and so on. Signs of agitation, restlessness, severe anxiety, ruminations on death, and hopelessness are all signs we watch for. Even more difficult can be making sure a patient’s apparent clinical improvement is not in fact the “peace of mind” some people feel before deciding to kill themselves.

Delusions

Delusions—the element of thought content most common in psychosis—have multiple subtypes:

They are sometimes categorized as “bizarre”, meaning either impossible, incoherent, or utterly fantastical; or “non-bizarre”, which are unlikely but less far out (“my neighbor hacked my cable and is putting audio recording devices around my house”). Delusions may align with the patient’s emotional state—e.g. someone with psychotic depression who believes he has somehow killed his own son—or have no apparent relation to their mood.

Delusions may also be classified by their content, e.g. paranoid, referential, erotomanic, persecutory, grandiose, religious, and somatic/bodily. To focus on one type for a moment: Referential delusions are when you think that coincidental or unrelated things have some special significance for you. For example, the day’s winning lotto numbers may contain a secret code, or the people crossing the street in strange patterns must be a portent of some kind. In other words, the salience of everything in the world as it relates to you increases dramatically. This overall feeling is common in psychosis, especially manic psychosis.

Another common cluster of delusions are those where one feels as if he is the passive victim of some form of psychic manipulation. Thought withdrawal is the feeling that another person or entity has somehow removed or stolen thoughts from one’s mind. Thought broadcasting is the feeling that others can see/read/know your thoughts, or that your thoughts are somehow publicly available. Thought insertion is the feeling that other entities are putting thoughts into your mind that are not your own. These symptoms speak to the fact that a core phenomenological feature of many forms of psychosis is a breakdown of the self-concept and the boundaries of the self-vs-world.

Below is an example of psychosis in which various forms of delusions are apparent. In her case we were unable to help her achieve any insight into her illness, likely because her schizophrenia had remained untreated for close to 30 years while she had lived like a hermit with her sister who we suspect also had schizophrenia.

Vignette:

Ms. P is a 55-year-old woman with chronically-untreated schizophrenia who was hospitalized for inability to care for herself and refusal to accept outpatient care. On first meeting I ask her to tell me about the circumstances that brought her to the hospital today.

“I was in California,” she begins, “it was 1998. I was at this motel having a party with Pamela Anderson, Drew Barrymore, and Denise Richards. We were doing eight-balls for a while, you know, but then things started to get weird. They bent me over and took out this scalpel and dug it into my lower back, you can see the scar here,” she turns around and opens the back of her hospital gown while miming stabbing herself in the back. No scar is visible. She yells “scalpel pushed in, scalpel pushed in” repeatedly as she imitates the alleged assault, a phrase we later asked about but for which we found no explanation. “They were at it all night, it was crazy, and they wouldn’t let me leave. Kind of like here, actually. By the way, how long have those cameras been recording me? I don’t want them reading my thoughts,” she says, gesturing to the camera in the hall.

“I think those cameras have a live feed for staff to observe the unit but they aren’t recording for playback later, but I can check on that for you. It’s reasonable to wonder if you’re being recorded,” I said.

“Sure,” she replied, rolling her eyes. “Anyway, how long are y’all going to bleed me dry in here? You want my blood? You want to steal my organs like those other hospitals? Just send me back to my husband’s place and I’ll be fine.”

“You’re married?”

“2700 Point Lane. That’s our address, you can check it. He said I could stay there.”

I pulled out my phone then and there to look it up. “This is Michael Jordan’s mansion,” I replied after seeing the first search result.

“Yeah, he’s my husband,” she replied, “when can you drop me off?”

10. Abnormal Perceptions

All perception is generated by the brain. Sensation usually refers to the process whereby a stimulus impacts a nerve in a sensory organ, which then transduces the energy from the stimulus into electrical information that travels to the brain for “further processing”. For example: the energy from photons hitting photoreceptor cells in the retina being converted to action potentials in the optic nerve. Perception is one result of that brain processing, when you say “I see a book in front of me”—it is what appears in consciousness as our brain’s best-guess “representation” of the outside world.

The primary kinds of abnormal perceptions are illusions—misperceptions based on actual sensory data—and hallucinations—perceptions generated internally by the brain without sensory input. Sometimes the experiences of derealization and depersonalization are included under abnormal perceptions as well.

For our purposes the most relevant abnormal perceptions are hallucinations. They can be pathological or non-pathological and can occur in any sensory modality, with auditory hallucinations being the most common. Common among non-pathological varieties are hypnagogic hallucinations, which occur as you transition from wakefulness to sleep and can be quite strange. Hallucinations are seen in psychotic disorders, substance use, alcohol withdrawal, delirium, epilepsy, migraines, sleep deprivation, and all kinds of neurological conditions like Lewy body dementia. Along with delusions and disordered thinking, hallucinations are one of the primary features of psychosis (although not all psychosis involves hallucinations).

In schizophrenia, for example, auditory hallucinations are often experienced as one or more voices talking. Importantly, these are perceptions, so it actually sounds like something to the patient. Typically, the hallucinations sound like they’re coming from “outside” the patient’s head, as opposed to an internal voice. The voices may have an identity or be mysterious. They vary in how articulate or intelligible they are. The voices may talk to the patient or to each other. They may be hostile or neutral but aren’t typically friendly or helpful. The voices may argue, yell at the patient, threaten him, comment on what is going on, or command him to do things (command hallucination are particularly concerning as some patients feel compelled to act on the commands). The voices may come and go, be persistent, or only be present during acute psychotic episodes. For many patients the experience is quite frightening and disorienting, and carrying on a normal conversation may be difficult or impossible.

11. Idiosyncrasies

Idiosyncrasies aren’t often included in a formal mental status exam, although I think they deserve a place. They may be revealing about someone’s personality, their approach to the world, and to other people. Idiosyncrasies may help with diagnosis, but are rarely strong enough to base anything on by themselves. That said, what may at first appear to be a series of idiosyncrasies might turn out to be signs of, e.g. high-functioning Autism (Asperger’s), schizoid or schizotypal personality, or less commonly a neurological disorder2.

It may not be clear at the outset whether some aspect of the patient’s presentation is due to their underlying character as opposed to an acute exacerbation of illness, so these are provisional at the outset.

Examples include: unusual sense of personal space, hyperreligiosity, odd sense of humor, highly moralistic, highly rigid, irritation as unusual things, excessive attention to detail, unusual interests/fascinations, affected manner of speaking, unusual clothing.

12. Cognition

Aside from orientation and alertness mentioned at the beginning, a basic cognitive exam should screen for impairments in attention, memory, language, and executive function. Depending on the situation we may also test calculation, visuospatial ability, abstract reasoning, naming and object recognition, or motor/praxis tasks.

For examples of some of these tasks I’ll refer you to the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. It’s copyright but a quick search can find it or other similar tests like the mini-mental state exam. Items covered include visuospatial/executive functioning tasks like drawing a clock and copying a cube, a naming task (identifying drawings of animals), memory (word recall), attention, language (phrase repetition), abstraction, and orientation. I may return to aspects of the cognitive exam in more detail later in the series.

13-14. Insight & Judgment

The patient’s insight refers to the degree of understanding he has about his impairment/illness and a concomitant need for treatment. Insight can be a philosophically and practically controversial topic, as Awais Aftab has written about here. For my purposes now, what’s important about insight stems from the basic understand of having an impairment and needing it fixed.

My own rough and ready way to divide up insight is into three groups, which in practice is really a dichotomy, since I’d say around 95% of us fall into groups (1) and (2):

Poor insight: those of us who don’t recognize the problem, or are in denial about it, or have such bizarre views about the impairment that it makes communicating with others about it almost impossible.

Fair insight: a basic recognition that there is a problem that requires treatment.

Good insight: rare. Usually reserved for people who are particularly psychologically minded, curious, and motivated to audit themselves with ruthless honesty.

Signs of improving insight depend on the degree of initial impairment. For a patient with schizophrenia, it may involve a basic acceptance of the diagnosis. For people with chronic interpersonal problems, insight might involve realizing their problem lies in their own behavior and not with everyone else. Insight may involve understanding the effects one’s illness has on others and not just oneself.

Many conditions such as depression don’t typically impair insight unless it progresses to psychosis. In cases where insight is not grossly impaired, our efforts may be focused on improving insight further, assuming the patient is interested in exploring that.

Judgment can be even more difficult to assess than insight, but we do our best. Working on an inpatient unit with the ability to observe patients day-by-day may give a better sense of someone’s judgment than a snapshot at a visit every few months. But what exactly do we mean by judgment? In its most narrow sense it could mean whether the patient is approaching their own medical problems reasonably. In this way it is analogous to insight, which is insight about illness specifically and not some kind of general insightfulness about life. This runs the risk, however, in judgment turning into “the patient agreeing with what I say”, which clearly isn’t the correct way to think about it. On the other hand, an overly-inclusive understanding of judgment asks too much of our patients, and my job isn’t to treat someone suffering solely from “poor judgment”.

On an inpatient unit, we look for signs of acceptably good judgment by observing whether the patient can interact with other patients and staff reasonably, is capable of basic conflict resolution, and is able to express medical preferences that are at least not obviously irrational. Some mental status exams recommend asking the patient various stock questions like “if you found a stamped and addressed envelope on the ground next to a mailbox, what would you do?” I’m not a fan of those kinds of questions, and prefer to assess judgment by talking through real-world problems, e.g. can the patient help formulate a reasonable plan for after leaving the hospital?

Insight and judgment may track one another, insofar as people tend to act more rationally regarding serious illness when they have an understanding that they’re sick. People often show apparent insight in what they say (“I admit I’m a gambling addict…”), but the ultimate test of insight is trying to act on the knowledge (…and I’m taking the following steps to deal with it”). For those with acute impairments, judgment often improves alongside insight (“OK, I now realize I was psychotic from binging on meth—I’d like more treatment so I can feel normal again”).

Up Next: Approaching the Interview, and the Chief Complaint…

There has been a big push to be watchful for depression during and after pregnancy, but there are other psychiatric syndromes that can develop in the perinatal period including mania, psychosis, panic disorder, and OCD. Sometimes this requires hospitalization, as the mother may be at risk for harming herself or her baby.

Inpatient psychiatric services for pregnant women are sorely lacking, as a good number of units will routinely deflect an admission due to fear of an adverse event during or after treatment, such as a miscarriage or birth defect. The result is that some non-trivial number of psychotic or suicidally depressed pregnant women have nowhere to go, possibly spending days held up in emergency rooms with no meaningful treatment. Needless to say this is a scandal.

Geschwind syndrome is a cluster of interesting behavioral and personality changes which affect some people with temporal lobe epilepsy. It consists of: (1) long-winded, digressive, or circumstantial thinking, (2) excessive writing (hypergraphia), (3) hyperreligiosity, (4) reduced sexuality, and (5) intense focus on mental and emotional life. Some have speculated that various religious figures, such as the Apostle Paul, may have had this condition.

Thanks for the (detailed) reminder of what it means to be a truly observant clinician. Reading this, I was reminded--in a good way--of the DSM, which at its best is a compilation of careful observations of the variety of ways humans tend to shift out of the "normal" range of the curve.

Thank you for this fascinating essay. I feel so lucky to have a healthy brain and a very manageable level of neuroticism.